emma safir

Emma Safir builds portals, blurring the bounds between tangible and intangible space. In this conversation, we talk about the feminine origins of digital technology, privacy, and the greediness of photography. Born in New York City, she now resides in Brooklyn.

I hope you enjoy our conversation. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.I hope you enjoy our conversation. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Artwork photos courtesy of the artist; artist portrait courtesy of Hannah Cash

Let’s start with an introduction to your practice.

I work with digitally printed fabrics and then I upholster them. I make the collages from photos that I’ve taken with analog cameras, disposable cameras, or digital cameras. I’m always looking to get the most out of an image. I don’t really know what “the most” means but it’s a visceral feeling.

The way I think of that, in terms of your practice, is that you seem to be pushing the two-dimensional into the three-dimensional, almost physicalizing the flat image.

That’s a really cool way to describe it. I do feel that I’m thinking in my head what it feels like when I’m trying to take a photo. It’s like creating that moment. I want to have the aura. That’s why I’m taking it apart and splicing it with other images and other moments in time.

Can we talk about using both digital and non-digital techniques?

The aesthetic of the machine and what it can do to the image are really interesting to me. I think about this idea of resolution, the quality of the image, and different modes of captured images. How much visually pleasing data can I get from it? If I shoot with film, I get a really beautiful, grainy texture when I zoom in. If I use my digital camera, it has crazy resolution and everything is hard. The iPhone is a step down. But also the eye can see things differently than the machine does. We see in RGB [red-green-blue] and the screen is RGB. When we make printed matter, it is in CMYK [cyan-magenta-yellow-black]. We have visual fluency between different color spaces.

Images are made up of many small parts, that’s what pixels are. We can see what the pixels are trying to realize. That’s what brought me to wanting to take apart the photos. I was making these paintings out of foam board; I would cut them apart and puzzle piece them back together. Smocking fabric became a way to take an image, put it back together, and take it apart, while having it be one continuous piece of material. The technique was originally invented to add stretch to garments before there was elastic. This idea of gathering something really tight to make it expand was interesting to me. That is so specific to what textile can do.

Raising Glitches III (detail), 2021, silk, MDF, neoprene, house paint, Flashe paint, upholstery foam, and appliqué, 57 x 37 x 1.5 inches

Does your process start with the photographs?

I have a photo archive of pictures I’ve been taking for the past fourteen years organized by when and where it was taken. I have some photographs I think about a lot. I’m always taking pictures with reflections in glass, fabric behind reflective glass, privacy stickers, people’s privacy solutions. I’m creating in the photograph a third space that only exists between the reflected and the transparency of the glass, compressing those spaces together.

In Photoshop, I manipulate several images on top of each other to expand this illusionary space and make it unidentifiable but also familiar. I then digitally print it onto silk and upholster the fabric onto the canvas. I usually leave them on the ground or have them on the wall and they reflect a colorful shadow. I am interested in both their autonomy and having a physical entrance into space.

Why do you choose to display them in those two ways?

They’re all either leaned or they have this inch-and-a-half cleat that creates a colorful shadow behind it. The silk is semitransparent so when I stretch it over the canvas, which is usually covered in a top layer of white or colored neoprene, it seems like it’s illuminated from inside, like a screen. They’re upholstered too. I think about their roundness, their relationship to the body, their libidinal presence, our collective relationship to fabric.

When we were kids, TVs were still convex and they were like furniture. You bought them at a furniture store. They radiated heat and static. Over the course of our lifetimes, they’ve gotten flatter to the point where now they’re concave. It’s like we are entering screen space instead of it entering our space. That relationship to the round thing that sits in the corner is really interesting to me as someone who spent a lot of time sitting too close to the television.

Right, televisions have changed not only the way they relate to space but also the way they take up physical space.

It’s taking up as little space as possible.

And it no longer feels like an object, it aspires to be unnoticeable.

You want it to be as least object as possible. That’s why they’re making ones that are mirrors or paintings.

I’m interested in something that can be both relational to a screen, which is so not related to the body, and to furniture, which is so related to the body. This is a tension that screens and phones have, especially the older TVs. The static! I would use static to stick little pieces of paper to the TV screen. I was like, I can’t believe this works! They still have this tactility that we deny them. New ones do get hot and my computer does make a noise when it’s tired. So I feel like these paintings exist in that in-between realm of undefined space between screen and body, physicality and digitality.

Installation view of Raising Glitches, Yale School of Art Gallery, New Haven, 2021

Let’s dig more into this digital aspect of your work. When I was introduced to your work through Adriana, she talked about your interests in digital labor and labor dynamics. How does that play out in your work?

Using the fabric and the digital is really important. These are intentional materials for what they represent. There is a broad misunderstanding of what digital labor is. In grad school, I had several conversations where people would re-explain my work to me and say, “and then you just print it”—as if the printing itself and the relationship between the machine and me and the things that happened in between have nothing to do with the final result. I’m interested in levels of mediation, from myself, and their relationship to digital or analogue space.

People think of textiles as something that’s completely unrelated to the digital sphere but they’re actually inherently linked together. Digitality is fundamentally a feminist invention, in terms of its relationship to weaving and the loom, where computers come from. That’s the origin of my insistence on using the fabric in a digital way but also doing these hyperanalogue techniques, like smocking or lacemaking. The really specific hand labor that I’m doing is a way to completely mediate something away from my hand, through many different lenses, via whatever I’m using to make the image, then Photoshop, and then whatever happens when it gets printed, steamed, and all the shit I do after that.

Both kinds of labor are undervalued in general. One because we associate it with simplicity. Digitization is supposed to make things easy and streamline our way of life. The other, like embroidery, is such a gendered labor within capitalism because it’s not considered to have any use value. Because it has no use value, it has no broader value.

When you say, digitality is a feminine invention, can you explain that?

Ada Lovelace wrote the algorithms for programs for jacquard looms. For a time in the twentieth century, women were literally referred to as computers—that was their job title—when they were working as administrative assistants, what maybe they would call now rather than secretary. Women were considered computers and eventually got replaced with literal computers. It’s an underrated labor. Weaving requires complicated equations to make shapes and determine how much yarn is needed. It’s a mechanized process.

What is more known is the relationship between men and hacking. Mindy Seu has written a really great book called Cyberfeminism Index that talks about these relationships in a much more eloquent way.

It’s interesting to surface that lineage, bringing textiles back into a relationship with a digital framework, especially because the latter has become so masculine-coded.

Motherboards are called motherboards. And they were first woven by women because of their “nimble hands.” Many of the small parts that sent the first rocket to the moon were made by, I believe, Navajo women.

I had no idea.

That’s not a known history. We’re so separated from how things are made. There’s this idea now that things are just made or they just appear. With companies making computer chips right now, we have no concept of the physicality and how it affects other humans. There’s this desire in mainstream culture to separate these things. But there are people finding ways to talk about it right now, like Mindy Seu and Julia Bryan-Wilson in her book Fray.

You said you were interested in “creating a third space that only exists between the reflected and the transparency of glass.” I’m curious about navigating the idea of the third space in a somewhat two-dimensional format. The theoretical idea of a third space is a space that’s between the home and the professional, an alternative space where you can gather. That’s more of an urban studies theory but it’s very physical and place-based.

This is a new thing that I’m thinking about—the desire for a physicality that doesn’t exist. That’s what the images are of. They’re capturing a thing that can’t exist. It’s a more ephemeral idea for me, a way of image making or capturing or manufacturing that feels not quite possible to obtain.

What do you mean?

Other than the photograph of the reflection, that space doesn’t exist. They’re different three-dimensional spaces that are reflecting each other. The photo is doing an impossible splicing of space, like a smashing together of multiple times and space. When I’m layering multiple reflections, it feels like I’m adding to that confusion but also not offering access to it because they’re difficult to decipher visually. It’s like an affective third space.

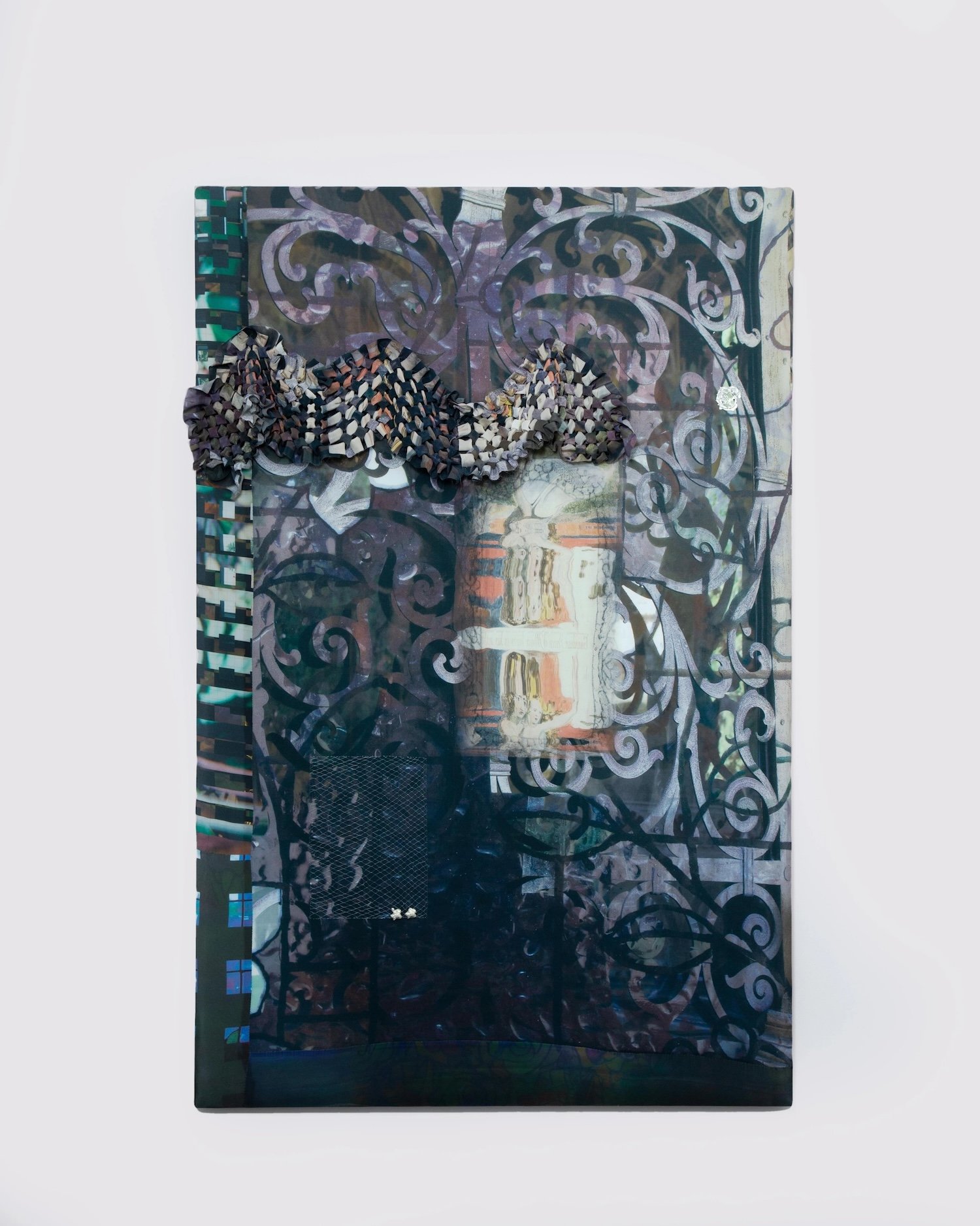

Red Devil (Cour d’Amour), 2024, silk, ultra lightweight MDF, neoprene, house paint, Flashe paint, upholstery foam, and appliqué, 57 x 37 x 1.5 inches

Can we talk more about what your photos are capturing?

Usually they are windows. A lot of them are privacy glass, something behind privacy glass, or textiles that are draped, like curtains. I really like printing fabric on fabric. For a while, I was taking images through pieces of fabric. I also take photos of privacy stickers.

Like the ones you put on a window to prevent someone from seeing in?

Exactly. Privacy glass is fascinating to me because you can’t see but you can see a little bit. They are also useful for light. It feels like a weird, voyeuristic tease. Privacy stickers are an aspirational idea of what is wealth or what is fancy interior. Since stained glass in churches, they’ve been bastardized. Stained glass was made to be psychedelic experiences for people who were not literate to keep their attention.

And now you can get them from Home Depot.

I see the same patterns all over the world. I always take pictures when I see them. Even just now, I was in Senegal and I saw this one sticker that I always see. I have pictures of it from everywhere. It was so thrilling to see it. It’s a visual language that everybody shares if they live in urban environments and are around lots of people and windows.

I can think of some very specific ones that I pass by. They can be practical or decorative, or both. But there’s a tension in drawing attention to—

Your private space—

People use it to create a barrier from the public or from outsiders and you’re bringing attention to that barrier. It’s also a facade, in the sense of its deceptiveness.

The fragility is really crazy to me. We’ve all just decided that it’s fine to have glass windows. This is an agreement that everyone has: that you’re not going to break it or you’re not going to peep in that person’s window. The desire for the private to be public and vice versa is a tenuous and shifting thing for people always. I started taking these pictures because I was spending a lot of time in Holland. Over there, they love to not have curtains. I think it’s rooted in an early Protestant thing, like look at us, we’re chill, we’re not doing anything bad.

We don’t have a reason to—

Right, there is no reason to be private. Everyone can know what we’re doing because everything is good. When people did have curtains or privacy glass, it felt really pointed. Then I started seeing it more broadly as I got less focused on Holland. It was a way to start thinking about privacy solutions but also the purpose of privacy. It’s protective but it can also be very dangerous.

People ask me, or they used to, if the photos that I am taking are voyeuristic. They don’t feel voyeuristic to me because I’m not deriving pleasure in taking these photos or looking in. But I am pursuing it. It’s a complicated thing.

That’s the tension. The photos are anonymous. You’re not capturing what’s behind them (since the point is one can’t access what’s behind them). They’re not identifiable since they are both zoomed in and then manipulated. You’re abstracting them. And yet, your object of focus is this attempt for privacy.

I always try not to have anybody in my photos. I don’t want to take their privacy in that way, that’s not interesting to me. As I continue to take pictures, I’ve been leaning more toward businesses. If I want to slow down and take a picture, I now feel invasive doing it to people’s windows. Storefronts feel like, in capitalism, open waters.

Is that an intentional shift?

I think it’s just the longer I’ve been taking pictures and seeing where I feel comfortable. I never take photos in New York.

Really? That’s surprising you’re not using where you live.

Well, I do it on my phone, just for me and for reference. When I am a tourist, it’s easier.

It’s more socially accepted as a tourist. You’re also seeing things differently and for the first time. Once you’ve walked down your Brooklyn street a million times, you’re not looking in the same way.

You make yourself very visible publicly in New York when you’re taking photos of things. I feel more comfortable doing it as a tourist. I don’t really like to take pictures. When I’m looking for the privacy moments, I’m actively looking to take pictures, which is hard for me to do. I need them and I want to have them but I feel anxious when I’m taking the photos, unless it’s really quickly taking a photo of someone’s chihuahua.

That again is a funny tension. You don’t want to be noticeable but your paintings are bringing attention.

It’s true.

And you’re still compelled to use photography.

It shifts over time. I didn’t used to feel that way as much. I think I’m more self-conscious. I consider more when I’m taking pictures. Photography can be really greedy. It’s so accessible. I don’t want to be greedy but I do want to capture these affective spaces and ideas of memory.

When I’m taking photos, I don’t take that many and I reuse a lot of photos over time. Those privacy glass ones from Holland are my prized privacy glass images and they get used a lot. I took a lot of time taking those pictures. They’re in focus and they’re good. I can sense when I wasn’t fully committed to trying to take a picture. That’s also why I use photography but don’t think of myself as a photographer. I’m more interested in it as an image apparatus. It’s a tool to create material to use for the broader painting.

Part of this interview series is that I’m asking each artist to direct me to the next. So, who is an artist working today that you are intrigued by, and what is it about their practice you’re intrigued by?

Tamen Perez also thinks a lot about photography but uses paint and paintbrushes. We’re both interested in the idea of image capture and reproduction. She’s been recently interested in making cameras and then scanning, digitizing, and inverting the images. I admire her unending search to reconcile image-making while the world is so urgently disintegrating around us. You can feel the urgency and insistence in her work.

Published July 14, 2024